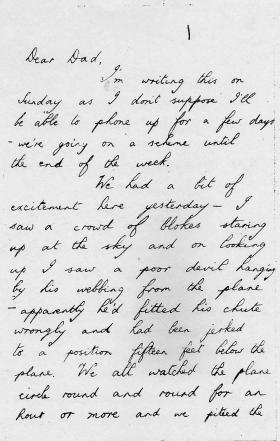

On very rare occasions a parachutist is unable, when jumping from a plane, to break away from the static line hooked up inside the aircraft, usually as a result of entanglement. Consequently, they are left suspended in mid-air trailing in the slipstream of the aircraft; this is known as a Hang Up.

The first recorded Hang Up in British airborne forces history occurred on 17 July 1941 at RAF Abbotsinch (the present day Glasgow International Airport) during a demonstration by members of 11 SAS Battalion, the embryonic airborne unit which later became the 1st Parachute Battalion of The Parachute Regiment.

The unfortunate paratrooper in this instance was a Cockney and former Grenadier Guardsman, Frankie Garlick. There were no evolved drills for Hang Ups at this early stage of airborne forces development. Cutting Frankie away would have resulted in certain death as British paratroopers did not carry reserves, and the crew of the converted Whitley bomber were unable to pull him back in.

The pilot, Edward Cutler, took the decision to land the plane with the tail of the aircraft held as high as possible in the air, and the hapless Para was dragged over the grass with the parachute on his back acting as a sled.

Amazingly, Frankie Garlick survived the landing with only cuts and bruises, although his parachute and pack were damaged beyond repair and both heels were ripped off his boots!

Two years later in North Africa, another Hang Up occurred which resulted in a gallantry award for an Assistant Parachute Jump Instructor. Trainees were jumping from a Dakota when one of them, Private Trevor, experienced a Hang Up. Efforts to haul him back in were defeated by the slipstream. With no reserve the paratrooper faced almost certain death if the static line was cut or failed. The prospects of success from landing the aircraft with Trevor attached looked equally slim.

In an outstanding and hair raising act of bravery, Sgt Instructor Cook shimmied down the static line to the unfortunate trainee while the aircraft was flying at about 800 feet. No mean feat considering that part of the line would have been jammed hard against the fuselage with the rest of it (and Trevor) bucking like a bronco in the wind currents.

Sgt Cook attempted to free Trevor from his perilous situation while gripping him with his feet. However, the buffeting and twisting in the slipsteam resulted in his own parachute starting to entwine round that of Trevor. Realising his predicament Cook made one final effort to free Trevor as he released himself. Cook was fortunate not to have a partial canopy collapse on the way down as five of the rigging lines on his parachute had been severed in the mid air melee with Pte Trevor.

Although Cook’s efforts to free Trevor were ultimately unsuccessful, this exceptional act of bravery resulted in Cook being awarded the George Medal later that year. Fortunately, the unlucky paratrooper was later hauled back into the aircraft.

On 18 March 1944, Sapper Wolfe of 591 (Antrim) Para Squadron RE witnessed a Hang Up. After circling in the air for an hour the aircrew flew out to Poole Harbour in Dorset and cut the parachutist loose into the sea. The unfortunate parachutist, Lt John A D Williams, did not survive.

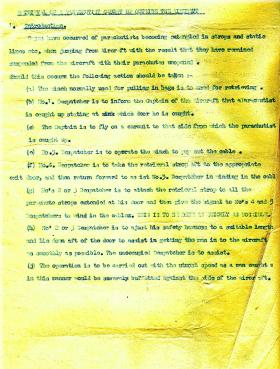

There is also an eye witness account, of a further Hang Up in Chaklala (India) in 1944, by an RAF Airgunner, which is listed below.

Another hair raising incident occurred when British, American and Canadian Airborne Forces acted as the spearhead for the Normandy landings in June 1944. Brigadier James Hill’s Brigade Major, Bill Collingwood, had been blown out of the floor exit in his Albermarle aircraft by enemy flak while hooked up.

He was left hanging upside down, spinning below the aircraft and entangled with a 60lb kitbag strapped to his right leg, with enemy flak bursting all around him. His plane limped back over the Channel and just before arriving over the English coastline he was safely pulled back on board.

On landing he commandeered a jeep, even though he was not fit, and with other men from the aircraft shot off to join the Ox and Bucks who were taking off in gliders for France that same evening. Thus the following day he was able to report to Brigadier Hill for duty in Normandy “with one leg stuck out sideways.”

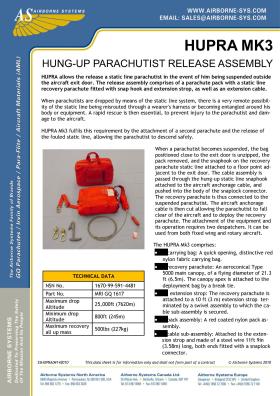

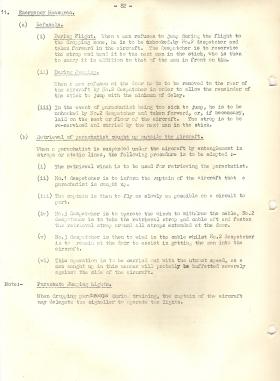

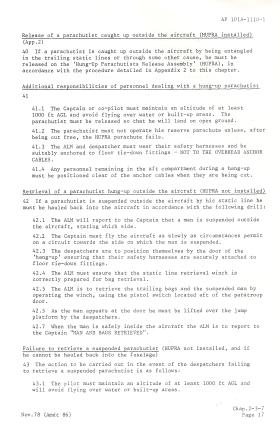

Modern military aircraft are now generally fitted with an electric winch cable, to retrieve a paratrooper with a Hang Up, and a HUPRA System (Hung Up Parachutist Release Assembly), which is used if the winch option is not feasible. Using the HUPRA, an emergency parachute is attached to the hung up paratrooper’s static line and the paratrooper is then cut away from the aircraft allowing him to safely descend on the emergency parachute.

Such technologies do not exist for those who are privileged enough to still jump from World War II air frames. In such an eventuality the parachutist has to hope that a manual cutaway of the static line and deployment of their reserve will see them safely to earth.

Latest Comments

There are currently no comments for this content.

Add Comment

In order to add comments you must be registered with ParaData.

If you are currently a ParaData member please login.

If you are not currently a ParaData member but wish to get involved please register.