When 1st Airborne Division deployed to Arnhem as part of Operation Market Garden, the Division was supplemented by nearly 600 Airborne medical personnel. Allied Commanders knew the conflict would lead to high casualties should 1st Airborne Division achieve their objective of seizing and holding the Bridge before being relieved by XXX Corps ground troops. After Airborne troops landed on 17-18 September 1944, the Battle did not go to plan. Fierce fighting led to very heavy casualties, their severity left little opportunity for evacuation and lost supply drops led to critically low medical resources. This situation presented a huge problem for the Airborne medics - and German commanders when casualties were eventually captured.

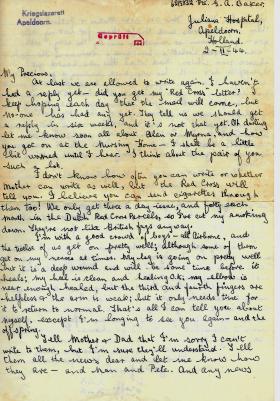

After the Battle, food, medical supplies and personnel to look after the 2,000 or so British and about 1,500 German wounded were in short supply. Despite their status as Prisoners of War, German Commanders had little option but to utilise Airborne medics to treat these casualties. What emerged was a British-administered Hospital established at Apeldoorn, near Arnhem which would later become known as the 'Airborne Hospital'.

Early Medical Services in Apeldoorn (17-25 September)

The Airborne Hospital was initially established through the efforts of two men; Capt Redman of 133 Parachute Field Ambulance and Lt Col Herford of 163 Field Ambulance

Captain Redman jumped on 18 September with 133 PFA. After injury during his descent, he was captured and sent to a Dutch hospital established at Apeldoorn. Following his own recuperation he offered his help. A fluent German-speaker, in about a week Capt Redman had become the official Liaison Officer between the local Dutch hospitals and was granted an Ambulance and complete freedom of movement.

Lt Col Herford, also fluent in German, was the Commanding Officer of 163 Field Ambulance. He had reached Nijmegen as part of the ground forces attempting to reach Arnhem. On 24 September 1944, Herford organised a medical relief mission from HQ Airborne Corps to Arnhem. He eventually met German officials, where concerns were being raised over treatment of the already numerous casualties at Apeldoorn. Herford initially persuaded Major Longland at the St Elizabeth's Hospital (an MDS in Arnhem established by 16 Para Field Ambulance) in the West of Arnhem to release resources and medics to Apeldoorn. On 25 September, Lt Col Herford was sent to Apeldoorn himself to visit the Chief Regional Medical Officer Lt Col Zingerlin.

Facilities in Apeldoorn expected an influx of wounded British soldiers following a truce agreed in Oosterbeek the previous day (for information on the temporary truce, refer to the article below). German-occupied hospitals in Apeldoorn were already near-capacity. Lt Col Zingerlin took Herford to a pre-war Dutch Army base, the Willem III Kaserne Barracks, where he suggested around 250 lightly wounded Airborne troops could be treated. The Barracks provided potentially excellent facilities with central heating, decent laundering facilities, good sanitation, a large kitchen designed to cater for two thousand and a bath house equipped with showers. Lt Col Herford reputedly recognised the potential of this facility immediately and suggested the Barracks should become ‘British Hospital’ staffed by British medics, to which Lt Col Zingerlin agreed.

Three Barrack blocks were assigned to the British. These blocks were three-storey buildings with an entrance hall, offices, toilets and wash rooms and each dormitory was contained thirty beds. All British wounded would be sent here until they could be sent to Prisoner Of War camps in Germany. German forces soon established an evacuation chain by ambulance and truck from Arnhem to Apeldoorn.

The 'Airborne Hospital' at Apeldoorn becomes operational

Later on 25 September, around 1,000 casualties and Medical personnel poured into the Barracks. Despite some early concerns among Airborne medical officers about Lt Col Herford, an unknown fluent-German speaking newcomer, his knowledge of German proved invaluable to help overcome numerous early differences of opinion. The 'Airborne Hospital’ came into being on 25 September 1944.

After Operation Berlin on the night of 25-26 September 1944, numerous Airborne casualties were left behind in the Arnhem area, along with the majority of the Airborne medics not already captured. Most of the wounded were moved from the Airborne MDS's at the Schoonoord Hotel, de Tafelberg and St Elizabeth’s Hospital to Apeldoorn during 26 September, boosting casualty numbers to about 2,000. Nevertheless, despite 'rough and ready' food and conditions and supply shortages, the Hospital was functioning effectively when Divisional ADMS Col Graeme Warrack arrived at around 1900 hrs on 26 September, who subsequently assumed command.

On 27 September, all wounded at St Elizabeth’s fit enough to travel were moved to Apeldoorn. 16 PFA staff who remained were also slimmed down from two Surgical Teams to one. Major Longland's team left, leaving Capt Lipmann-Kessel's team behind to care for the thirty or so patients left. Lipmann-Kessel was assisted by Capt Brian Devlin (RMO 7th Battalion The King’s Own Scottish Borderers, who had been captured on 21 September but was allowed to work at St Elizabeth’s Hospital), Padre D McGowan and a small number of Other Ranks.

Col Warrack established an Airborne Hospital HQ, Registrar's Office, an Administrative Wing responsible for staff, food, supplies, sanitation and discipline, and a Medical Wing responsible for treatment and allocation to the wards, operating theatres and the transfer of patients across other medical facilities in the Apeldoorn area. The HQ consisted of the following:

HQ Commander: Col Graeme Warrack Second-in-Command: Lt Col Herford Liaison Officer: Capt Redman Registrar: Maj Miller (staffed by administrative clerks available). Administrative Wing Commander: Lt Col Marrable, assisted by WO1 Len Bryson. Medical Wing Commander: Lt Col Alford.The majority of the medical personnel came from 181 Airlanding Field Ambulance, but 16 and 133 Para Field Ambulances were also represented, together with several Regimental Medical Officers (RMOs) from various units. Col Warrack later recorded a staff of just under 300 medical personnel.

German Medical Services were to supply medical supplies and fuel, although food was scarce. Fortunately, some vital Airborne Medical equipment taken to Arnhem proved very satisfactory, especially the accumulator-operated spot lamps and the paraffin pressure lamps. The penicillin supply (which the Germans called 'mouldy cheese' and viewed with some suspicion) lasted about a week, although it was carefully conserved. Col Zingerling soon promised to supply basic items such as sheets, blankets, soap, towels, bed-pans and urinals. German resources were also stretched dealing with their own casualties, although German High Command refused to allow special medical air supply drops to alleviate this.

Plasma supplies were consistent however, and the Germans provided some of the numerous medical supplies originally destined for 1st Airborne which had not reached them during the Battle. German Commander also agreed X-ray patients and more serious cases could be transferred by German ambulance into two local Dutch hospitals with more acceptable surroundings, better food and treatment from Dutch nurses, surgeons and doctors (who had been refused access to work directly in the Airborne Hospital).

Col Warrack later reported the Germans provided a great deal of help after being impressed by the fighting spirit and gallantry of 1st Airborne Division, and the willingness of the British to help themselves, although this may have been influenced by a desire to appear even-handed should any Allied advance reached their position.

The Dutch also helped by providing English books, playing-cards, soap, towels and other sundry items. A daily supply of blood was arranged by the head of the local Dutch Red Cross, Dr Trip, who also arranged for a Dutch nurse to smuggle out a message asking the RAF if they could attack the railway network around Apeldoorn, so as to try and slow down the evacuation of casualties.

Camp transit - to prison camps or to escape?

On 26 September nearly 500 walking wounded, with ten accompanying RAMC personnel, marched to the railway station bound for a cattle truck train and transport to Germany. The size of the task facing the Medical Services can be gauged by the fact that despite this exodus, another 700 arrived that day.

A regular routine was established to keep patients for as long as possible, although the German authorities tried to prevent this. Germans continually pressed the Registrar and his staff for a complete list of the wounded in Apeldoorn. Considerable 'embroidery' in these returns enabled men to escape without being missed and ward Medical Officers(MOs) and the CO often tried to assist escapees. Whilst German officials tried to confiscate all maps and compasses, a number escaped their searches and maps were copied numerous times. Guards patrolled the site, and the camp was surrounded by concertina wire and a ten-foot steel fence. On the eastern side however, there was only a barbed wire fence beyond which lay open fields. Whilst SS troops guarded the hospital initially, they were soon replaced by regular German soldiers - many of whom were rather old and (and were quickly nick-named the ‘Bismarck Youth’). The effect of the replacement of younger guards with older men, combined with the increasing fitness of the Airborne soldiers led to a steady stream of escapees through the eastern side of the hospital.

The Dutch also helped by providing English books, playing-cards, soap, towels and other sundry items. A daily supply of blood was arranged by the head of the local Dutch Red Cross, Dr Trip, who also arranged for a Dutch nurse to smuggle out a message asking the RAF if they could attack the railway network around Apeldoorn, so as to try and slow down the evacuation of casualties.

By 29 September their were 796 recorded casualties at Apeldoorn, although by 2nd October the number had risen to 1230 as casualties from the surrounding area arrived. This influx led German Commanders to insist 250 patients, with two dozen medical staff leave by 'hospital train'. In reality, this consisted of cattle tracks with straw bedding. Despite Col Warrack's protestations, the transit went ahead, followed by another of nearly 500 men followed on 5 October, leaving just 103 at Apeldoorn before the final arrivals from the surrounding hospitals. They also included the the party from the MDS at St Elizabeth's which had remained in Arnhem until 13 October, when they were sent to Apeldoorn at short notice taking their remaining patients with them. One soldier had been operated on the same morning and was still under the effects of an anaesthetic.

The Dutch also helped by providing English books, playing-cards, soap, towels and other sundry items. A daily supply of blood was arranged by the head of the local Dutch Red Cross, Dr Trip, who also arranged for a Dutch nurse to smuggle out a message asking the RAF if they could attack the railway network around Apeldoorn, so as to try and slow down the evacuation of casualties.

On the night of 16 October, Lt Col Herford, Maj Longland, Capt Lipmann-Kessel and Padre McGowan all escaped under cover of bad weather during two separate attempts, using the cover of a filthy night. The next day Col Warrack escaped after disappearing into a 'hidey hole'. The Hospital was subsequently restricted to one block, under the command of Major S Frazer, the Second-in-Command of 181 Airlanding Field Ambulance.

Closing of the Airborne Hospital

The Airborne Hospital finally closed on 26 October 1944. Without warning Major Frazer was instructed all remaining personnel would be transferred to the local St Josefstichting Hospital. Within an hour ambulances arrived. The remaining casualties, some of whom were still in a serious condition (including one who was given a blood transfusion during the move from a female Dutch camp follower who acted as a willing donor), were moved to St Josefstichting Hospital in Apeldoorn. When patients conditions improved or suitable hospital trains were available, the wounded were moved to internment camps in Germany. The St Josefstichting continued as a POW hospital, run by the few Airborne RAMC personnel still available from October 1944 until April 1945. Although this placed a heavy strain and limited resources on a small number of medics, it probably lead to rather better treatment for wounded POWs than those in German facilities.

The Willem III Kaserne Barracks is still in use by the Dutch Army, to train Military Policemen. A plaque erected in the 1990s outside Col Warrack's former Office commemorates its part in the Battle of Arnhem.

Suggested further reading for the 'Airborne Hospital':

Niall Cherry, Red Berets and Red Crosses (1999), Robert Sigmond Ltd Alexander Lipmann-Kessel and J St John Surgeon at Arms, (1976) Leo Cooper Graeme Warrack, Travel by Dark: After Arnhem (1963) Harvill Press: LondonWith assistance from Niall Cherry

Source: With thanks to Niall Cherry

Read More

Latest Comments

There are currently no comments for this content.

Add Comment

In order to add comments you must be registered with ParaData.

If you are currently a ParaData member please login.

If you are not currently a ParaData member but wish to get involved please register.